CATEGORIES

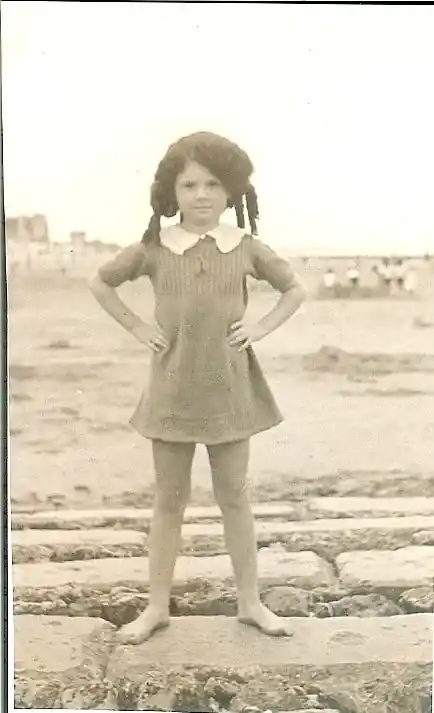

Breaking Stereotypes | People We Admire | Women EmpowermentI was born in Paris, France in 1926. My parents were refugees from Russia having fled the revolution. Our home was a Russian enclave. We only spoke Russian. We only had Russian friends. Our food was Russian. Even the newspaper was in Russian.

The story of my life is being an outlier. I was always from somewhere else; wherever I was, I never fit in. On the playground in Paris, I was seen as the Russian girl. When I was living in the United States, I was seen as the French girl. When I lived in Switzerland, I was the American woman. Then when I finally returned to the States, I was the Swiss professor. My parents believed that education was speaking several languages, so by the time that I turned six, I was already fluent in French, Russian, and German.

At the end of 1939, my father decided that it was not safe for us to stay in war-torn Europe. We were lucky to board the last ship from Europe, the SS Saturnia. After a 10-day ocean crossing, we arrived in the United States and were interviewed on Ellis Island. None of us spoke English. It was a difficult time for my parents, my six-year-old brother, and I.

We were in California when France fell. I attended Beverly Hills High School where I learned Spanish. I graduated in 1944 and went on to Scripps College. Within three years, I graduated with a major in philosophy and a minor in psychology by going to summer school at UCLA and UC Berkeley. At 17, I wanted to live independently from my parents. I left for New York where I shared one room with a girlfriend. The rent was $50 a month; I needed a job that would pay at least $200. I found one with Flexalum Venetian Blinds.

I was dating a young man by the name of Sam Josefowitz who also spoke French, German, and Russian. He was involved in a mail order start-up company. Sam and I got married and traveled extensively throughout South America organizing his mail order company, the “Record of the Month” and the “Book of the Month” clubs. This venture turned out to be successful so we expanded these clubs in Europe, Asia, and the middle East—for a total of 22 countries.

While traveling in Switzerland I got pregnant. We came back to New York where we lived in a basement apartment. I remember the window was next to the ceiling and all you could see were the feet of the people passing by. We needed a larger apartment and found one for rent on Central Park West. In 1950 I gave birth to a daughter and 21 months later to a son.

My life’s work began when I was hired as a research assistant by Dr. Peter Neubauer, Director of the Child Development Center. My new job was to find psychiatrists and psychologists who were writing on child development to see if they had any interest in spending a month studying the children living in a Kibbutz in Israel. The following year I spent a month co-facilitating a series of workshops with Dr. Neubauer for 20 healthcare professionals from Europe, U.S. and Israel studying child care in various Kibbutzims.

Back in New York, I was instrumental in placing the children abandoned by their parents in hospitals (known as well babies) into foster care homes within a matter of days. This program remains in place today; this was the impetus for me to continue my education. I applied to the Columbia University School of Social Work. The cut off age was 36—I was 35 and nine months; I was their oldest graduate student ever. Three years later, I earned my Master’s degree in clinical social work.

We moved to Lausanne in the summer of 1965 as Sam wanted our children to attend the same school as he had. I got a job as a social worker in a child guidance clinic. I also taught the first course in case work in Switzerland. At the age of 48 I received my Ph.D. in social psychology.

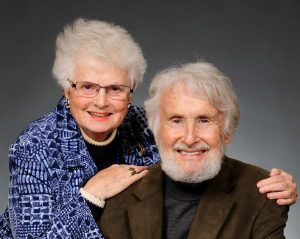

In 1972, while at the clinic, I met an American professor of economics, Dr. Herman Gadon, sent by Harvard to start a satellite business school in Switzerland. He needed a social worker to help him with a consulting job at a local hospital and asked me to join him. We worked together as consultants with various profit and nonprofit organizations. After a year and a half, we had fallen in love. By then, both my children were attending American universities. Dr. Gadon asked me to join him at the University of New Hampshire (UNH) where he was part of a faculty starting their new business school.

In 1974, I left my husband Sam to move to Durham, New Hampshire, to be with Herman. I became a member of the business faculty at UNH. As the only female faculty member, many of my female students would come to my office to talk about the issues they had with discrimination and harassment. Women needed help with very different work issues such as family and career, the glass ceiling, being a single mother, etc. This was the incentive to teach a course for women in management; this was the first such course in the country.

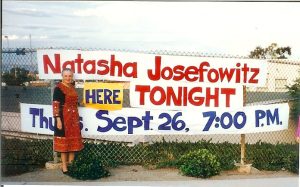

I wrote articles concerning issues women were facing in the world of work which were frequently published in business journals and women’s magazines. Addison Wesley Publishing Company offered me a contract to write a book based on my course work. My first book, Paths to Power: A Woman’s Guide from First Job to Top Executive became a best seller. It was adopted by over 100 colleges and universities. At UNH I organized a group of women members, “Concerned Women Faculty;” we addressed student issues. I instituted workshops in supervisory training for UNH employees. I was invited to speak and consult in the United States and Europe as my book was translated into half a dozen languages. I consulted with the FBI, the CIA, and other large and small companies, using humorous verse to counteract the initial reluctance to study this topic of women entering work places where they were not welcomed.

On Herman’s sabbatical in 1979, a friend offered her house for rent in a place called La Jolla, California. We spent a delightful winter on the beach and decided not to return to ice and snow. San Diego State University hired me as a member of their College of Business faculty, where I continued teaching my classes in women in management. Herman was employed as a Professor of Economics at the UC San Diego.

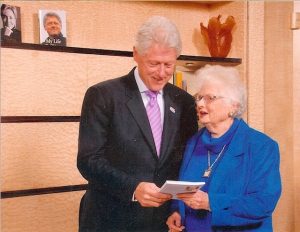

In addition to teaching, I went on writing both business and humorous verse books while I continue with my public speaking and made many media appearances. In 1980, I wrote a weekly column for a local paper, The San Diego Business Journal, followed by the San Diego Daily Transcript. Next I was syndicated by Copley News Service and I also wrote for La Jolla Light. In 2015 I was inducted into the San Diego Women’s Hall of Fame. Several interesting opportunities developed: I became the sexual-harassment expert for the City of San Diego for three years. Jonas Salk asked me to facilitate a seminar on creativity. (His wife, Francoise, illustrated my first poetry book.) After we both retired from teaching, I was hired as a lecturer on a variety of cruise ships, every year traveling to a different part of the world for three and a half months.

Currently I am writing a bi-monthly column for the La Jolla Village News as well as the San Diego Jewish World, an international publication. To date, I have written 21 books. The more recent ones are on retirement, and after the loss of my husband, Herman, I wrote a book called “Living Without the One You Cannot Live Without”. Within a short period, I lost my son, my younger brother, and my son-in-law.

I am 95 years old and continue to be active as a speaker, writer, consultant and guest on TV and radio shows. I have six great-grandsons and live in a retirement community where I am involved in a variety of committees as well as serving on community boards. I look forward to the next chapter of my life with great wonderment. My motto is: “Identify the fear and then go there.” The meaning of life for me is one word: “service.” The first part of my life was about empowering women; now it is empowering older folks like me. The greatest gift you can give an old person is to make them feel useful.